Of all the classes of asteroid my favourite (if it is possible to have a favourite astronomical object) is ‘the Centaurs’. This is probably because of my work – more years ago that I wish to mention – on the orbital motion of the first two objects of this class.

De toutes les astéroïdes mes préférés sont les Centaures. C’est peut-être parce qu’il y a longtemps, j’ai fait des études sur le mouvement orbital des deux premiers objets de cette classe.

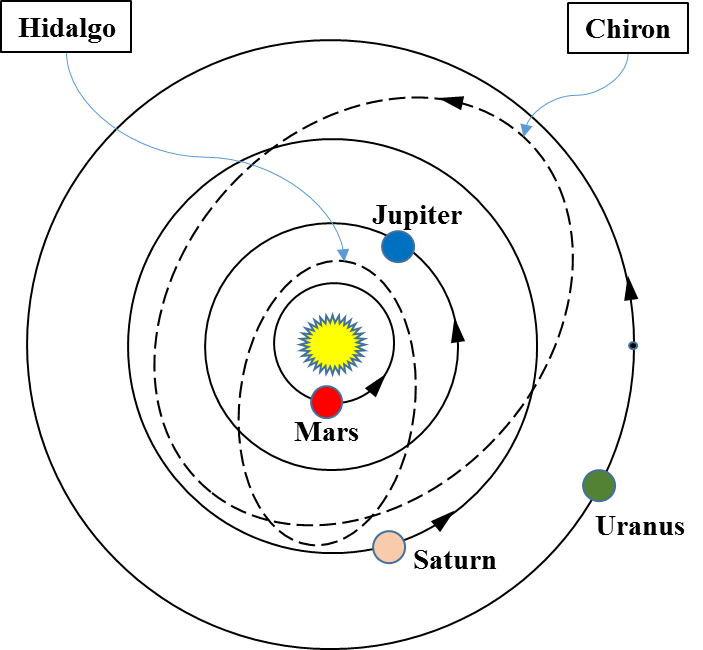

Orbiting predominately between the orbits of Jupiter and Neptune, and with semi-major axes ranging from ~5.5 to ~30AU, the first of this class to be discovered was 944 Hidalgo. Detected by Walter Baade (b.1893 d.1960) on 31st October, 1920 whilst working at the Hamburg Observatory, Hidalgo is on a relatively (for the class) high eccentric orbit (e = 0.66). It has a perihelion distance (of 1.95 AU) a little beyond the orbit of Mars, and an aphelion (of 9.53 AU) close to the orbit of Saturn.

En orbite entre les orbites de Jupiter et Neptune, et avec un demi-grand axe d’entre ~5.5 to ~30AU le premier centaure découvert fut 944 Hidalgo. Détecté par Walter Baade (b.1893 d.1960) le 31 octobre, 1920 pendant qu’il travaillait à l’observatoire de Hamburg, Hidalgo a un orbite est fortement excentrique (e = 0.66) et un distance périhelique (of 1.95 UA) un peu au delà-de l’orbite de mars, et une aphélie (de 9,53 UA), proche de l’orbite de Saturne.

Next to be found was 1991 DA (5335 Damocles). To date, there have now been a total of 490 objects classified as centaurs. Except for Hidalgo (which is named after a Mexican priest), the 25 centaurs which have been given proper names are (mostly) sourced from the half-human/half horse centaurs of Greek mythology.

Centaurs are asteroid-like objects in orbits with semi-major axes between 5.2 and 30 AU (the orbits of Jupiter and Neptune respectively). Orbital parameters for all known centaurs range from: 5.5 < a < 30.1AU; 0.01 < e < 0.94; and 1.42 < i <175.2º, with around 10% on retrograde orbits.

The centaurs are on unstable orbits and have short dynamical lifetimes (a million to ten million years) compared to the age of the solar system (~4.5 x 10**9 years). Their orbits change significantly due to gravitational interactions of the major planets (which can put these objects on hyperbolic, i.e. solar system escape, paths) and collisions with the major planets and other centaur objects. This means that their individual lifetimes within the solar system are astronomically short.

They have comet-like orbits, and the sources of these objects are most likely to be both orbital period reduction of long period comets following major planet gravitational interaction, and outward migration of asteroid belt objects under the influence (in particular) of Jupiter and Neptune. (Studies into the gravitational effect of Jupiter on the outer-main belt have shown that a second rarefied belt of asteroids can exist between the orbits of Jupiter – Saturn.)

Many centaurs can also be thought of, at least in part, as transition objects between comets and asteroids. Spectroscopic observations and analyses of both Hidalgo and Chiron would suggest that these are comet transitions, their spectra are more like comets rather than other asteroids. As with all things in astronomy, the picture is not totally clear as the estimated sizes of these objects (~40km and 140 – 170km respectively) are an order of magnitude larger than a typical comet nucleus.

Next month

The search of the Vulcanoids!