The observatory at Joliment, Toulouse (1841-1981)

The city of Toulouse

Our first morning in Toulouse was spent in the muggy summer rain exploring the city centre, its shops and impressive landmarks. However, in the afternoon of the 21st August 2019 the skies of Toulouse cleared and the blazing summer sun began to heat the day and light up the colourful architecture that lends this city the name ‘la ville rose’ (the pink city).

Toulouse is an ancient city with attractive buildings from all eras adorning its squares and streets. The rain may have spoiled the photograph below somewhat, but it didn’t diminish the real thing. Today the most famous building in Toulouse is the Capitole, a magnificent structure dominating the main square, which houses the town hall and a theatre. The construction of this emblematic building began in 1190 and it never ceases to impress visitors.

In character and ambiance Toulouse possesses a vibrant, energetic and multicultural vibe. The centre is compact and easy to navigate. At average walking speed you can easily wander from the main train station (la gare de Toulouse-Matabiau) to the central Capitole and shops. Then it only takes a short time to meander along to the banks of the river Garonne, cross the Pont Neuf and explore the district of Saint Cyprien, a quirky little area scattered with afro hairdressers, small cafes, a secondhand bookshop and small exotic grocers.

The city of Toulouse

Our first morning in Toulouse was spent in the muggy summer rain exploring the city centre, its shops and impressive landmarks. However, in the afternoon of the 21st August 2019 the skies of Toulouse cleared and the blazing summer sun began to heat the day and light up the colourful architecture that lends this city the name ‘la ville rose’ (the pink city).

Toulouse is an ancient city with attractive buildings from all eras adorning its squares and streets. The rain may have spoiled the photograph below somewhat, but it didn’t diminish the real thing. Today the most famous building in Toulouse is the Capitole, a magnificent structure dominating the main square, which houses the town hall and a theatre. The construction of this emblematic building began in 1190 and it never ceases to impress visitors.

In character and ambiance Toulouse possesses a vibrant, energetic and multicultural vibe. The centre is compact and easy to navigate. At average walking speed you can easily wander from the main train station (la gare de Toulouse-Matabiau) to the central Capitole and shops. Then it only takes a short time to meander along to the banks of the river Garonne, cross the Pont Neuf and explore the district of Saint Cyprien, a quirky little area scattered with afro hairdressers, small cafes, a secondhand bookshop and small exotic grocers.

The observatory at Joliment

Next stop was a visit to see the historic astronomical observatory located in the gardens of the district of Joliment, This 'suburb' is a mere 15 minute gentle uphill stroll north east of the train station, but if you don’t want to walk you can take the metro line from Marengo and it takes about a minute from stop to stop. Those who do make the way on foot will have the pleasure of wandering through the modern Marengo area with its modern library and apartments to emerge at the foot of the gardens. As you enter this green space you pass a children’s play area and eventually find yourself in shaded parkland which soon leads to the historic observatory buildings. The French adverb ‘joliment’ means prettily, and certainly this area and even the astronomical buildings are very attractive. You will find yourself in surroundings more reminiscent of a country manor house than a scientific institution.

Next stop was a visit to see the historic astronomical observatory located in the gardens of the district of Joliment, This 'suburb' is a mere 15 minute gentle uphill stroll north east of the train station, but if you don’t want to walk you can take the metro line from Marengo and it takes about a minute from stop to stop. Those who do make the way on foot will have the pleasure of wandering through the modern Marengo area with its modern library and apartments to emerge at the foot of the gardens. As you enter this green space you pass a children’s play area and eventually find yourself in shaded parkland which soon leads to the historic observatory buildings. The French adverb ‘joliment’ means prettily, and certainly this area and even the astronomical buildings are very attractive. You will find yourself in surroundings more reminiscent of a country manor house than a scientific institution.

There are several astronomical buildings at Joliment but the main one is pictured below, in the sunshine finally. This main part of the observatory building began construction in 1841. It was designed by the architect Urbain Vitry, and along with three other buildings at Joliment, is registered as a historic monument.

A little further down this page is a brief history of the observatory at Joliment, but first I should mention the surprise visit we were given to explore inside the observatory itself. We had only planned to have a look around the outside of the buildings, but we were lucky enough (during my partner's 'trespassing'!) to have a chance encounter with the president of the Société d'Astronomie Populaire (Society for popular astronomy), which is the renowned Toulouse astronomy club founded in 1910. He was kind enough to enthusiastically show us the round the buildings and the impressive historic equipment housed there.

The SAP de Toulouse was founded to popularise astronomy among the general public and to offer amateur astronomers the chance the make the most of their interest. This endeavour seems to have been a great success, and due to its history as a leading observatory there is plenty of equipment for visitors, members and schools to look at here. The observatory remains active and very well maintained, holding weekly events run by very knowledgeable volunteers for members. Most Friday evenings the public can visit and on the last Friday of each month there are free lectures to visitors given by a professional astronomer.

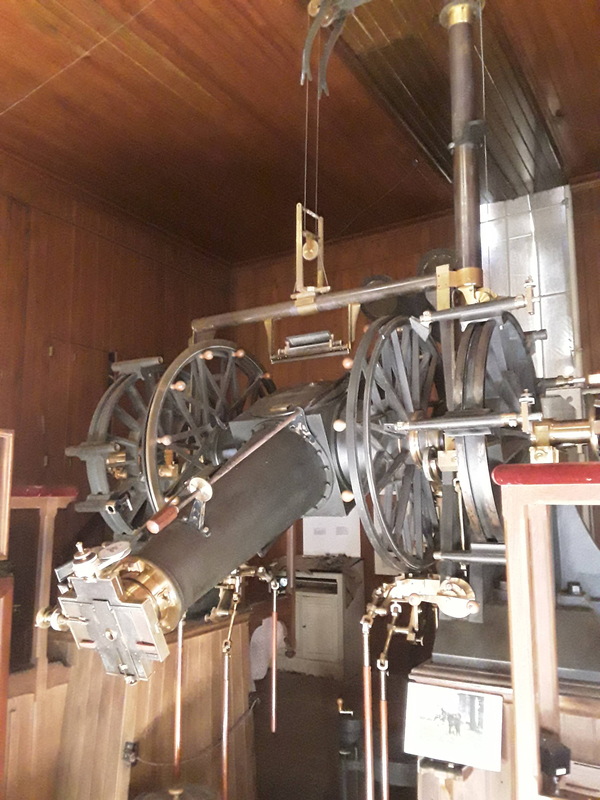

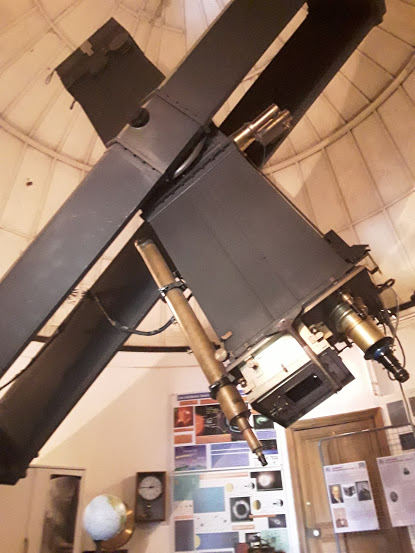

Below are photographs of the equipment housed at Joliment.

The SAP de Toulouse was founded to popularise astronomy among the general public and to offer amateur astronomers the chance the make the most of their interest. This endeavour seems to have been a great success, and due to its history as a leading observatory there is plenty of equipment for visitors, members and schools to look at here. The observatory remains active and very well maintained, holding weekly events run by very knowledgeable volunteers for members. Most Friday evenings the public can visit and on the last Friday of each month there are free lectures to visitors given by a professional astronomer.

Below are photographs of the equipment housed at Joliment.

From left to right: Meridian telescope 1891; Equatorial telescope 1889; outside on the roof at Joliment

A history of the observatory at Joliment, Toulouse

Although this observatory has a fascinating history, its establishment does not mark the beginning of the history of astronomy at Toulouse. The first Toulouse astronomers were working and researching in the 17th century, and the earliest observatory in the city was built in one of the towers of the ramparts in 1733, and led by an astronomer called François Garipuy (1711-1782).

Toulouse already had an excellent reputation for being knowledgeable about this science, so much so that the astronomer Jérôme de Lalande (1732-1807) said of Toulouse ‘c’est de toutes les villes de province celle où l'astronomie est la plus cultivée’ (1792). At that time Toulouse already had about ten astronomers and three observatories.

The observatory at Joliment was active from the mid-nineteenth century, and during this century there were several directors whose lives and works would shape the renown of Toulouse as a centre of astronomy.

Frederic Petit (1810-1865) was the first director at Joliment but he had a very stressful time getting things up and running. He had been director at the previous observatory situated in rue des Fleurs since 1838, but as that building was in a bad state of repair he asked for a new one to be built. In those days Joliment lay just outside the city and was a more rural setting than it is today, so it was a very good place for observing the skies. After many initial problems, in 1841 construction on the new observatory began, but it took another six years before the place was finished, and four more before it was fit to work in. Once the observatory was fit for purpose Frederic began work. He drew up twilight tables for the regulation of street lighting; then in 1849 he worked out a method of determining the position of shooting stars. He could also be credited with introducing the tradition of popularising astronomy as he began to organise courses for the public. Sadly he died in 1865 and his successor Theordore Despeyroux left the position of director after only three months.

But all was not lost at Toulouse, and a new director, Pierre Daguin (1814-1884) from Poitiers was appointed as director at Joliment in 1866. He had studied at the Ecole Normale Supérieure, obtained a doctorate in 1847, and worked as a professor of physics at the Toulouse Faculty of Sciences for 20 years before his appointment. The observatory was still not well equipped but Daguin decided it should have a new lease of life, and ordered the large 80cm Foucault telescope, but unfortunately this was not delivered until 1875. On the fall of the empire in 1870 Daguin had a dispute with the town council who wanted to dismiss his concierge for having Bonapartiste views and he resigned.

By the early 1870s once the Franco-Prussian war was out of the way the new government wanted France to regain confidence in all areas. So during this decade French astronomy which had been based mainly in Paris (and its off shoot in Marseille) began to develop elsewhere too. More observatories were founded and the government began to invest more in the one at Toulouse.

Although this observatory has a fascinating history, its establishment does not mark the beginning of the history of astronomy at Toulouse. The first Toulouse astronomers were working and researching in the 17th century, and the earliest observatory in the city was built in one of the towers of the ramparts in 1733, and led by an astronomer called François Garipuy (1711-1782).

Toulouse already had an excellent reputation for being knowledgeable about this science, so much so that the astronomer Jérôme de Lalande (1732-1807) said of Toulouse ‘c’est de toutes les villes de province celle où l'astronomie est la plus cultivée’ (1792). At that time Toulouse already had about ten astronomers and three observatories.

The observatory at Joliment was active from the mid-nineteenth century, and during this century there were several directors whose lives and works would shape the renown of Toulouse as a centre of astronomy.

Frederic Petit (1810-1865) was the first director at Joliment but he had a very stressful time getting things up and running. He had been director at the previous observatory situated in rue des Fleurs since 1838, but as that building was in a bad state of repair he asked for a new one to be built. In those days Joliment lay just outside the city and was a more rural setting than it is today, so it was a very good place for observing the skies. After many initial problems, in 1841 construction on the new observatory began, but it took another six years before the place was finished, and four more before it was fit to work in. Once the observatory was fit for purpose Frederic began work. He drew up twilight tables for the regulation of street lighting; then in 1849 he worked out a method of determining the position of shooting stars. He could also be credited with introducing the tradition of popularising astronomy as he began to organise courses for the public. Sadly he died in 1865 and his successor Theordore Despeyroux left the position of director after only three months.

But all was not lost at Toulouse, and a new director, Pierre Daguin (1814-1884) from Poitiers was appointed as director at Joliment in 1866. He had studied at the Ecole Normale Supérieure, obtained a doctorate in 1847, and worked as a professor of physics at the Toulouse Faculty of Sciences for 20 years before his appointment. The observatory was still not well equipped but Daguin decided it should have a new lease of life, and ordered the large 80cm Foucault telescope, but unfortunately this was not delivered until 1875. On the fall of the empire in 1870 Daguin had a dispute with the town council who wanted to dismiss his concierge for having Bonapartiste views and he resigned.

By the early 1870s once the Franco-Prussian war was out of the way the new government wanted France to regain confidence in all areas. So during this decade French astronomy which had been based mainly in Paris (and its off shoot in Marseille) began to develop elsewhere too. More observatories were founded and the government began to invest more in the one at Toulouse.

The astronomer lucky enough to become director of Toulouse during this new era was Felix Tisserand (1845-1896) who was also a graduate of the Ecole Normale Supérieure. He took the position in 1873 after gaining some excellent experience as assistant astronomer at the Paris Observatory.. He was only 28 but he made the astute move of choosing to have two assistants at Toulouse: Joseph Perrotin (1845-1904) and Guillaume Bigourdan (1851-1932). The budget at Toulouse was much more limited than in Paris but Tisserand had the good sense to adapt the research at Toulouse to suit the limited means of the observatory; hence the astronomers there spent much time studying and researching the theories of celestial mechanics, And as time went on Tisserand's excellent reputation spread which helped to improve the financial situation so that he was able to make the Toulouse Observatory a real centre of astronomical activity.

Tisserand had the 83cm telescope installed in 1873 at the Toulouse Observatory. The wooden mount, however, was not sufficiently stable to enable photography, so the astronomers at Toulouse could only use visual observations. As a part of their work they observed the satellites of Jupiter and Saturn. Their work on these satellite systems was so good that Benjamin Baillaud, Tisserand’s successor at Toulouse, used it to establish a theory of the orbits of the then five known satellites of Saturn.

Perrotin spent time observing sun spots using a 108mm diameter reflecting telescope manufactured at the Marc Secretan’s optical and telescope factory in Paris. This telescope was equipped with a micrometre eyepiece (within which two crossed reticles are arranged in order to measure small angles of separation). Perrotin and the other observatory staff used this to measure sunspots on an image of the sun projected onto a screen behind the eyepiece. The archives of the observatory at Toulouse still house the magnificent drawings from their daily work on the surface of the Sun.

Perrotin also discovered six asteroids during his career; his first was found on 19 May 1874 and named 138 Tolosa. (138 refers to the fact it is the 138th asteroid found. (The first asteroid to be found, Ceres on the 1st January 1801, is formally designated 1 Ceres). At the time it was traditional for asteroids to be given female names, but Perrotin proposed (and had accepted) its name to be Tolosa after the ancient French (Occitan) language name for Toulouse. Bigourdan was in charge of meridian observations, observing the satellites of Jupiter, comets and sunspots and searching for dwarf planets (asteroids).

Tisserand had the 83cm telescope installed in 1873 at the Toulouse Observatory. The wooden mount, however, was not sufficiently stable to enable photography, so the astronomers at Toulouse could only use visual observations. As a part of their work they observed the satellites of Jupiter and Saturn. Their work on these satellite systems was so good that Benjamin Baillaud, Tisserand’s successor at Toulouse, used it to establish a theory of the orbits of the then five known satellites of Saturn.

Perrotin spent time observing sun spots using a 108mm diameter reflecting telescope manufactured at the Marc Secretan’s optical and telescope factory in Paris. This telescope was equipped with a micrometre eyepiece (within which two crossed reticles are arranged in order to measure small angles of separation). Perrotin and the other observatory staff used this to measure sunspots on an image of the sun projected onto a screen behind the eyepiece. The archives of the observatory at Toulouse still house the magnificent drawings from their daily work on the surface of the Sun.

Perrotin also discovered six asteroids during his career; his first was found on 19 May 1874 and named 138 Tolosa. (138 refers to the fact it is the 138th asteroid found. (The first asteroid to be found, Ceres on the 1st January 1801, is formally designated 1 Ceres). At the time it was traditional for asteroids to be given female names, but Perrotin proposed (and had accepted) its name to be Tolosa after the ancient French (Occitan) language name for Toulouse. Bigourdan was in charge of meridian observations, observing the satellites of Jupiter, comets and sunspots and searching for dwarf planets (asteroids).

After Tisserand left Toulouse for a position back in Paris it was Benjamin Baillaud (1848-1934), also a graduate of the Ecole Normale, who became director of the Toulouse observatory on the 18 March 1879. He had to recruit a new team of astronomers for both Perrotin and Bigourdan had moved on to new pastures soon after Tisserand’s departure. The team appointed by Baillaud consisted of Dominique Saint-Blancat (1880), Louis Montangerand (1883), Frederic Rossard (1888), Eugene Cosserat (1889), Emile Besson (1892) and Henri Bourget (1893). Most of these astronomers worked for four decades at Toulouse carrying out meridian observations. Montangerand who worked on astro-photography managed to photograph the ring nebula (in the constellation of Lyra and near to Vega, the fifth brightest star in the sky). This excellent photograph took nine hours of exposure and showed more than 5000 stars. The astro-photographers working with Baillaud took many good quality pictures and as a result the Toulouse Observatory was awarded the gold medal of the Paris Universal Exhibition of 1900, known as the Exposition Universelle de Paris. This vast 1900 Exhibition was a big fair that aimed to celebrate the achievements of the past century and lead the city forward into the next. There were many new inventions on display as well as architecture and art.

Baillaud was director of Toulouse for almost thirty years before returning to the Paris Observatory. At Toulouse he initiated two big projects which enhanced the life and work at the Toulouse observatory: the Carte du Ciel (map of the sky) and the construction of a telescope at the Observatory of the Pic du Midi. He also managed to spend some time teaching at the University in Toulouse during this time. Like his predecessor he was a talented and industrious director.

He believed that the instruments available at the observatory were not good enough for high quality astronomy. So he acquired three new instruments: a Brunner lunette (refractor) with an objective lens of 25cm in diameter which would mainly be for observing double stars; a double refractor in 1890 for both visual and photographic work, and also a meridian lunette in 1891. These two latter instruments would be used for carrying of the mapping of the skies project. He also managed to finance the replacement for the wooden mount of the 83cm equatorial with a metal mount in 1889. This telescope would be used by Henri Bourget to take photos of nebulae and between 1926 and 1935 it would be used for searching dwarf planets.

Baillaud’s time at Toulouse was very much dedicated to the Carte du Ciel project. This project had been started in Paris by Mouchez in 1889 and it was one of the first large scientific projects which entailed international cooperation. It would occupy the Toulouse observatory for more than half a century. The carte du ciel would have 22000 photographs taken and would involve 18 observatories including Paris and Bordeaux.

Due to the vast number of calculations needed for the giant Carte du Ciel project Baillaud called for females skilled in maths and calculations to help out. These 'dames de la carte du ciel’ were known as ‘calculatrices'. The situation of these talented women was often fascinating. They were well educated women with various qualifications, seeking supplementary income for differing reasons. Their appointment didn’t go through the usual channels; they would write a letter of application putting forward their qualifications and the reasons why they were looking for employment. Of course they were advantageous to the observatory in that they were less well paid than men.

Although the Carte du Ciel project was a big venture the advances it contributed to astronomy were very modest considering the time it consumed (it took 60 years to complete when it was supposed to take about 15). However, the advantages of this project for Toulouse were that Baillaud was able to provide another brand new instrument for the observatory: a double astrograph, which didn’t cost them anything; and also for many years he and his successors received plenty financial support due to the project. This gave the Toulouse observatory an excellent national and international standing. In 1908 Baillaud left his position at Toulouse as he was appointed director of the Paris Observatory where he remained until his retirement in 1926.

Baillaud was director of Toulouse for almost thirty years before returning to the Paris Observatory. At Toulouse he initiated two big projects which enhanced the life and work at the Toulouse observatory: the Carte du Ciel (map of the sky) and the construction of a telescope at the Observatory of the Pic du Midi. He also managed to spend some time teaching at the University in Toulouse during this time. Like his predecessor he was a talented and industrious director.

He believed that the instruments available at the observatory were not good enough for high quality astronomy. So he acquired three new instruments: a Brunner lunette (refractor) with an objective lens of 25cm in diameter which would mainly be for observing double stars; a double refractor in 1890 for both visual and photographic work, and also a meridian lunette in 1891. These two latter instruments would be used for carrying of the mapping of the skies project. He also managed to finance the replacement for the wooden mount of the 83cm equatorial with a metal mount in 1889. This telescope would be used by Henri Bourget to take photos of nebulae and between 1926 and 1935 it would be used for searching dwarf planets.

Baillaud’s time at Toulouse was very much dedicated to the Carte du Ciel project. This project had been started in Paris by Mouchez in 1889 and it was one of the first large scientific projects which entailed international cooperation. It would occupy the Toulouse observatory for more than half a century. The carte du ciel would have 22000 photographs taken and would involve 18 observatories including Paris and Bordeaux.

Due to the vast number of calculations needed for the giant Carte du Ciel project Baillaud called for females skilled in maths and calculations to help out. These 'dames de la carte du ciel’ were known as ‘calculatrices'. The situation of these talented women was often fascinating. They were well educated women with various qualifications, seeking supplementary income for differing reasons. Their appointment didn’t go through the usual channels; they would write a letter of application putting forward their qualifications and the reasons why they were looking for employment. Of course they were advantageous to the observatory in that they were less well paid than men.

Although the Carte du Ciel project was a big venture the advances it contributed to astronomy were very modest considering the time it consumed (it took 60 years to complete when it was supposed to take about 15). However, the advantages of this project for Toulouse were that Baillaud was able to provide another brand new instrument for the observatory: a double astrograph, which didn’t cost them anything; and also for many years he and his successors received plenty financial support due to the project. This gave the Toulouse observatory an excellent national and international standing. In 1908 Baillaud left his position at Toulouse as he was appointed director of the Paris Observatory where he remained until his retirement in 1926.

This takes us to the life of Joliment in the 20th century. During the years between the two wars the Carte du Ciel project was continued and daily work included the study of clocks and chronometers; and taking meteorological data. In 1935 an astrophysics service was introduced, and spectroscopic observation of stars was carried out. From this point on there would be a new generation of astronomers and astrophysicists whose work led directly to present day astronomical discoveries.

In 1981 it was decided that observations would no longer take place at Joliment due to increasing light pollution as the city increased in size. At this time the observatory staff moved the university campus at Rangueil, Toulouse and has since joined up with the Observatory of the Pic du Midi, to become the Observatoire Midi-Pyrénées (OMP) not far from the centre of Toulouse.

In 1981 it was decided that observations would no longer take place at Joliment due to increasing light pollution as the city increased in size. At this time the observatory staff moved the university campus at Rangueil, Toulouse and has since joined up with the Observatory of the Pic du Midi, to become the Observatoire Midi-Pyrénées (OMP) not far from the centre of Toulouse.