First and foremost, please do not ever, under any circumstance, look at the Sun directly through any normal telescope or binoculars. The intensity of the light will cause blindness instantly. Indeed, looking at the Sun with just our eyes for more than a fraction of a second will cause pain and at the very least temporary blindness. At sunset and sunrise, the intensity of the light is, reduced – but the same advice remains. Other than falling over in the dark, serious eye damage through careless or accidental solar observation is, today, one of the thankfully few occupational hazards of the traditional astronomical observer.

The Sun has been observed of course by all sentient creatures since time immemorial, and the diurnal (daily) and seasonal changing pattern of its position has been known to humankind since prehistoric times. Megalithic and Neolithic era (4000 to 3000BC) standing stones and stone circles, such as the famous sites at Carnac in France and Stonehenge in England have such distinct celestial and solar alignments that their positioning must have been in part, if not in full, for astronomical purposes.

Mais d’’abord nous allons parler brièvement de l’histoire de l’observation du Soleil. Mais il ne faut jamais regarder le Soleil directement au télescope ou aux jumelles. C’est très dangereux même pour quelques secondes et peut provoquer la perte de vision permanente.

Depuis des temps immémoriaux les gens ont observé le Soleil et sa position changeantse selon les saisons. A cause de leurs alignements distinctifs on croit que des sites célèbres comme Carnac en France et Stonehenge en Angleterre (4000-3000 av J-C) sont liés à l’étude des phénomènes astronomiques.

The immense radiation intensity and glare of the Sun severely restricted pre-telescopic observers and it befell, to Johannes Kepler to use the concept and technology of the camera obscura. This uses a pinhole to ‘project’ the image of the Sun onto a small darkened room/area. In 1607, as part of his work on understanding planetary motions, Kepler had been taking observations of the planet Mercury as it approached its inferior conjunction. Using a camera obscura, on the 28th May of 1607, Kepler believed that he had witnessed part of a transit of the planet Mercury. Several years later however, and after other observers had announced their telescopic observations of sunspots, Kepler realised that what he had observed was in fact a large sunspot group rather than Mercury.

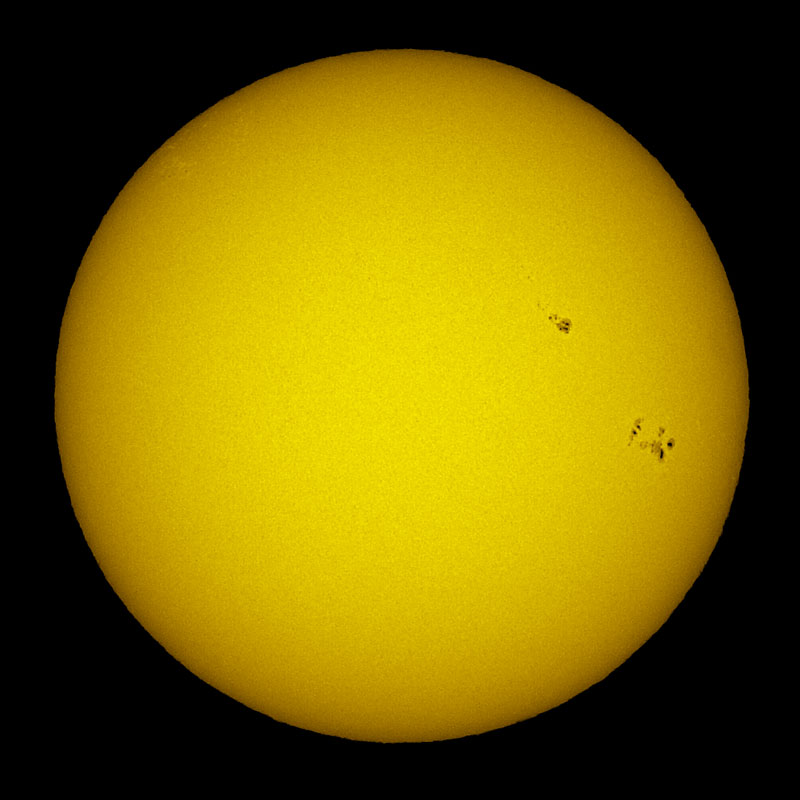

showing Sunspots on the photosphere

The identity of the first person to use a telescope to take solar observations in this way is lost in the mists of time, and whilst several 17th century scientists claimed to be first, no one will ever know. Both Galilei Galileo (b.1564 d.1642) in Italy and Thomas Harriot (b.1560 d.1621) in England were taking solar observations by this means in December of 1610. Other notable early solar astronomers include Christoph Scheiner (b.1573 d.1650), and father and son David (b.1564 d.1617) and Johannes (b.1587 d.1616) Fabricius, all of whom were recording sunspot numbers from March 1611 onwards.

The nature and location of sunspots was subject to some considerable debate. Their solar nature was challenged by the idea that they could be objects transiting, or orbiting between the Earth and the Sun. The discovery of the moons of Jupiter had leant considerable support to the latter argument. In 1642 the Bohemian optician and astronomer Anton Rheita, best known for his developments of the terrestrial telescope, his map of the moon and observations of the cloud bands of Jupiter, observed a large sunspot group for eight days during June of that year. Rheita, an advocate of the Tycho model of the solar system, promoted the view that sunspots were planets superimposed above the solar disc.

The Aristotelian perfection of the heavens was widely held and supported by the established Church. Any unproven ‘scientific results’ indicating the contrary and which could be explained by other means were difficult to accept. These challenges in reality are the nature of all scientific advances. Science and theories must be robust and resilient to strenuous examination. Many fundamental developments – for example: gravitation, nuclear physics, quantum mechanics and relativity, all seemed unbelievable when first proposed. The sunspot nature dispute was resolved to its solar nature by Galileo who demonstrated observational evidence for the spots originating, evolving and disintegrating on the solar ‘surface’.

The latter half of the 17th century saw the establishment of the great national observatories of Europe. Sponsored by King Louis XIV (the ‘Sun King’) the Paris Observatory was founded in 1642 and led by its first director, Giovanni Cassini. In England, the Royal Observatory at Greenwich was commissioned in 1675 by King Charles II, and John Flamsteed (b.1646 d.1719) was appointed as the first Astronomer Royal. His title was originally ‘Our Astronomical Observator’. The Astronomer Royal title was first formally bestowed upon was George Airy in 1838, the 7th holder of the position, although the term was in common usage from the 1770s. These observatories were primarily founded for geodetic purposes and to solve the problem of longitude navigation at sea.

The Berlin Observatory – latter to become famous for the discovery of the planet Neptune in 1846 by Johann Galle (b.1812 d.1910) – was established in 1700 by the mathematician Gottfried Leibniz (b.1646 d.1716) and, under the petitions of the astronomer Johann Encke (b.1791 d.1865) and geophysicist Alexander von Humboldt (b.1769 d.1859) subsequently expanded greatly under the patronage of King Friedrich Wilhelm III.

During the early 18th century many astronomers took solar observations and recorded sunspots. These included Ignatius Koegler (b.1680 d.1746), Andre Pereira (b.1689 d.1743) and Johann Weidler (b.1691 d.1755) in Germany; Pierre Le Monnier (b.1675 d.1757), Nicolas Delisle (b.1688 d.1768), the Italian born Giovanni Cassini (b.1625 d.1712) and his son Jacques Cassini (b.1677 d.1756) in France, and James Bradley (b.1693 d.1762) in England to name just a very few.

Perhaps one of the most prolific solar observers ever was the German astronomer Heinrich Schwabe (b.1789 d.1875). During his almost continuous 17-year daily recording of sunspot activity started in 1826, Schwabe took 12185 observations and made 8486 drawings. In 1844 he published his identification and recognition of the ‘solar cycle’, the approximately 11-year cycle of solar activity.

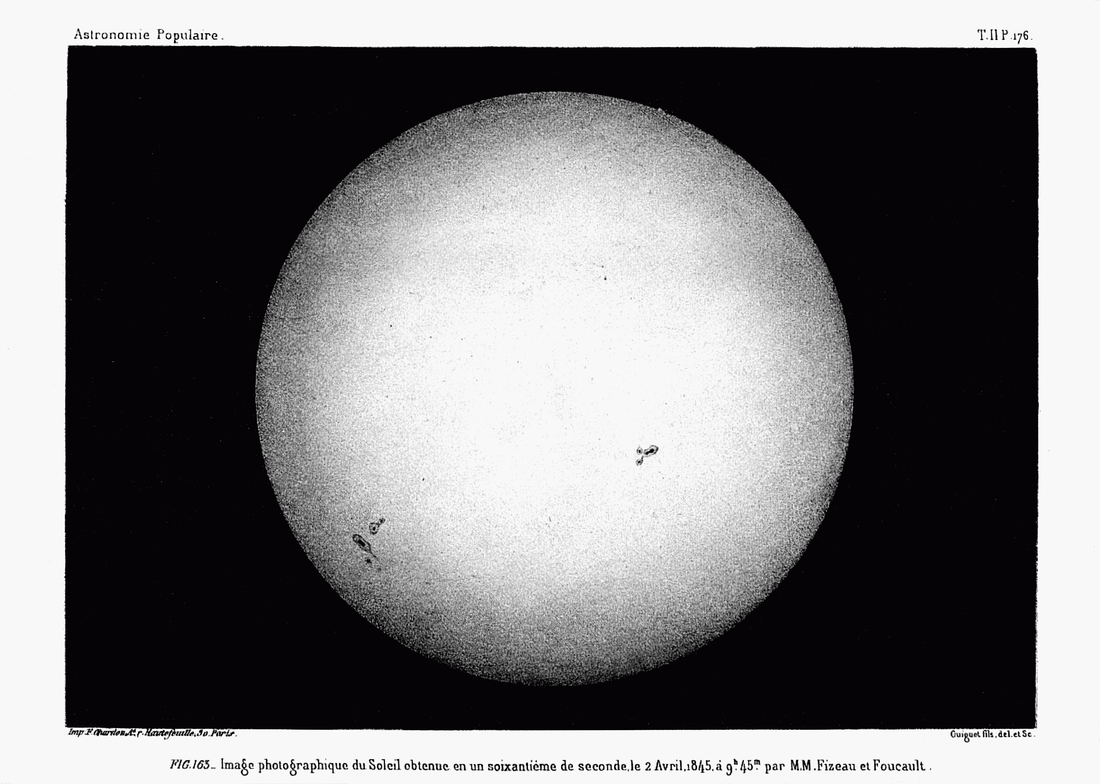

April 1845 saw Leon Foucault (b.1819 d.1868) and Hippolyte Louis Fizeau (b.1819 d.1896) make the first successful telescopic photograph of the Sun. Working under the support of the ninth Director of the Paris observatory, Dominque Francois Arago (b.1786 d.1853), they applied the advances they had made to the emerging science of photography and their resulting work clearly showed sunspot groups.