Our first Competition! The prize of a signed copy of our latest book: François Félix Tisserand – forgotten genius of celestial mechanics is on offer to the fortunate person who wins our free-to-enter competition. Everyone correctly answering the following question will go forward into our prize draw…

Where were the parents of François Félix Tisserand married?

To enter please use our competition entry form here. The draw for the winner will be made at noon on the 269th birthday anniversary of Pierre Simon Laplace (23rd March 2018) and the winner will be notified via email on that afternoon. The prize will be sent very shortly afterwards and no postal surcharges will be applied if the winner is living outside the UK.

Note: If you purchase a copy of our biography of Tisserand then you will be automatically entered into our prize draw. If you are the winner, full purchase and postal costs of your book will be refunded to you.

In this month’s blog we return to the Sun. Having discussed gravitation, pressure, emissions, radiative and convective energy transfer process, we now begin a more descriptive (i.e. less maths!) series looking at the structure, visible features, and atmosphere of our star.

Nouvelles

Notre premier concours! Nous avons décidé d’organiser un concours gratuit et le prix sera un exemplaire signé de notre dernier livre François Félix Tisserand – forgotten genius of celestial mechanics offert au heureux gagnant. Chaque personne qui donne la bonne réponse à la question suivante sera inscrit à notre tirage au sort:

Où a eu lieu le mariage des parents de Félix Tisserand?

Pour participer, merci de utiliser notre formulaire ici. Le tirage aura lieu à midi le 269e anniversaire de Pierre Simon Laplace (samedi 23 mars).

A Noter: Si tu achète un exemplaire de notre livre sur Tisserand, vous serez automatiquement inscrit pour le tirage, et si vous gagnez les frais d'affranchissement et le prix du livre vous seront remboursés

Ce mois nous reviendrons sur le Soleil. Nous avons déjà parlé de la gravité, la pression, les emissions et le transfer d'energie radiatif et convectif, mais nous allons commencer une série plus descriptive (moins de maths) où nous considérons la structure, les caracteristiques visibles et l'atmosphere de notre étoile.

In April we saw how the Sun produces its energy, in May we saw how the gravitational and pressure forces are generally in balance and mean the Sun is in Hydrostatic equilibrium, and in June we talked about convection heat transfer. This month we will see how these all ‘fit’ into the structure of the Sun. We begin by presenting an overview of the current model of the structure for the Sun.

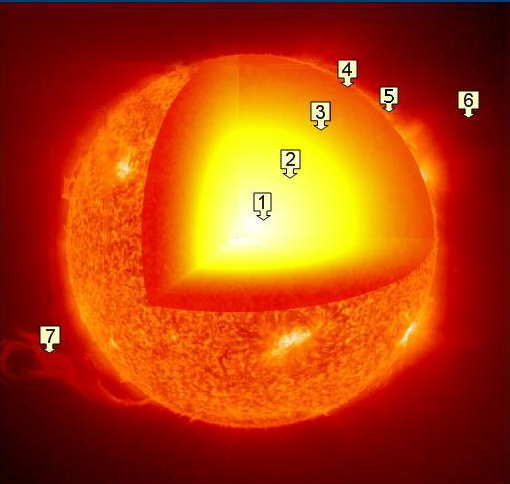

In this picture, which is based upon a photograph of the sun taken at the H𝝰 wavelength (654nm, the extreme red part of visible light spectrum), the key components are marked numerically and refer to:

- The Core; where fusion reactions generate the energy of the Sun’s emissions. The core extends approximately 25% of the Sun’s radius outwards, has a central temperature of around 16 million Kelvin, and a density around twenty times that of iron. As we saw in April’s blog, this is where hydrogen is fused to create helium. A small amount of matter in each individual fusion is converted to energy and, in doing so, vast quantities of energy are produced by mass conversion. Some energy is also produced by early-stages of the Carbon-Nitrogen-Oxygen fusion process.

- The Radiative zone of the Sun. Here energy from the core flows outwards and is transported by radiative processes; no convection takes place within this region. No fusion or energy generation process takes place within this zone. The radiative zone, where the matter is almost completely ionised, accounts approximately for the region from 25 to 70% of the Sun’s radius. Temperature reduces in this zone from 7 million at the extent of the core to about 2 million Kelvin at the start of the convection zone. Density similarly reduces from three times that of iron to about one fifth that of water over the same space.

- The Convection zone; this as the name suggests is the region where energy transport is dominated by convection energy transport processes, and as per the radiative zone, no energy is created in this area. The transition region between the radiative and convective zones is called the Tachocline; this is most likely to be the source of the Sun’s powerful magnetic field. The convection zone is (relatively) cooler and less dense than the radiative zone and as such is not completely ionised; elements such as Carbon, Nitrogen and Oxygen can retain some electrons. This, and the effect it has on the Sun’s opacity, is the trigger for convection to take place. We will see in future blogs, when we considering pulsating stars, the importance and dynamics of ionisation layers and the effect this has on a star’s opacity. The convection zone takes us from the radiative zone ‘up’ to the visible photosphere where the density has now reduced to 2 x 10**-7 that of water.

- The Photosphere is the visible ‘surface’ from our perspective and observations. As we have mentioned in previous discussions, it is not a solid surface but the region of the Sun where the density becomes sufficiently opaque (moving inwards; or transparent if moving outwards) for us to see a visible surface. It extends for a thickness of about 500km – tiny compared to the scale of the Sun. It is the region upon which we see features such as sun-spots: slightly cooler areas where areas of magnetic flux and forces disrupt the convection process; and the solar granulation, the seething convection cells bubbling up from the solar depths.

- The Chromosphere; an area where the temperature again starts to rise; from 6000 Kelvin in the photosphere to now around 20,000 Kelvin in this irregular ‘lower-atmosphere’. The higher temperature generates atomic emission lines; especially in hydrogen and the region is most frequently, but definitely not solely, observed at H𝝰 wavelength. The chromosphere (‘colour-sphere’) is the region within which prominences and flares are seen.

- Corona; historically observed at solar eclipse times (but more usually nowadays by using an equivalent instrument called a Coronagraph), the corona is the outer atmosphere of the Sun. At an unexpectedly high temperature, circa 1 to 3 million Kelvin, this layer of the solar atmosphere is almost completely ionised.

This low density (10**-12 times that of the photosphere), high-temperature plasma most likely gains its thermal energy from interactions with the solar magnetic field. Outer regions of the corona become dominated by thermal and radiation pressure and, overcoming the gravitational potential (for which we can read: escape velocity), high energy particles (electrons, protons and helium nuclei) flow outward from the sun at up to 900km/second. This flow is called the solar wind and can have a significant effect upon the Earth

The solar wind, ‘powered’ by the Sun’s magnetic field, extends the Sun’s atmosphere into what is named the Heliosphere. The heliosphere takes us outward up to the edge of the Sun’s ‘sphere of influence’ the boundary of the Sun’s magnetic field called the Heliopause.

At the heliopause, the solar wind particles lose the effect of the Sun’s magnetic field and reduce in velocity to subsonic speeds as they enter inter-stellar space. The Voyager 1 spacecraft (a multi-planet probe launched in September 1977) was placed on a hyperbolic (escape) orbit with respect to the Sun and crossed the heliopause in August 2012, at around 121 AUs from the Sun. - Eruptive features. Perhaps the most dramatic of all features visible on the Sun are the prominences and flares. We will look at spicules, eruptive and quiescent prominences, and flares – the most energetic events we can observe of the Sun. The energy released, even from relatively modest sized flares, if ‘aimed’ towards us can cause significant disruption to modern life. Flares pose a real risk to both space travel and potentially life here on Earth.

We will continue our blog over the next few months looking at detail into each of the major components of the Sun, with just an introduction to each here now. On our way we will review the temperature, pressure and density conditions within the Sun and show how we can estimate these fundamental properties. We will take a brief look at the emerging science of helioseismology (asteroseismology when applied to other stars) and how this can and has been used to inform us of the Sun’s interior. The nature and source of the Sun’s magnetic field(s) will be considered and we’ll see the effects these have on observational features and the solar atmosphere.

Further reading

(In ascending level of technical complexity)

[1] The Sun – Shining light on the Solar System. Neil Taylor. 2017

https://www.observatoiresolaire.eu/solar-physics.html

Next Month

Having considered atmospheric retention for the Earth last month, we will start our more detailed discussions on the structure of the Sun next month by looking at the solar atmosphere, and specifically the Corona. Next month’s blog will be issued on Saturday 31st March.