Ceres was discovered on the 1st of January 1801 by the Italian astronomers Giuseppe Piazzi (b.1746 d.1826) and, often overlooked, Niccolo Cacciatore (b.1770 d.1841). Working at Palermo observatory, Sicily, Piazzi (the observatory director) and his assistant astronomer Cacciatore were updating and correcting the Taurus region of the Palermo star catalogue.

A two-person task, Piazzi was observing and relaying observations to Cacciatore to record. They detected and recorded an object which had not previously been seen. Further observations over the following nights showed the object was moving against the background of stars and by March 1801 its nature as a new astronomical body within the solar system had been established. It takes its name from the Roman goddess of agriculture.

L'astronome Giuseppe Piazzi, directeur de l’observatoire de Palerme (1746 -1826) et Niccolo Cacciatore (1770 -1841) son adjoint, ont découvert Ceres pendant qu’ils étaient en train de mettre à jour la catalogue d’étoiles de Palerme.

Piazzi faisait les observations et Cacciatore prenait des notes quand ils ont observé un objet se déplaçant sur la voûte céleste. D’abord ils l’ont pris pour une comète. L’objet a été établi comme un nouveau corps céleste du système solaire en mars 1801. Ceres tient son nome la déesse romaine de l'Agriculture.

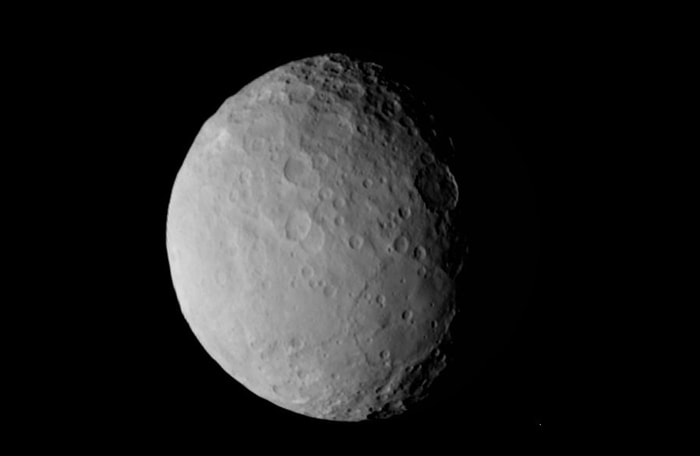

Imaged by NASA/Dawn mission on 19th February 2015 from 46,000km

On March 28th in the following year, Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers, (b.1758 d.1840) whilst observing from Bremen and cataloguing stars within the Virgo constellation, partly to aid recovery and monitoring of Ceres, detected a star-like image which he was sure had not been there in the January. He observed the object for several hours and could detect its proper motion within that timescale. Olbers had discovered the second asteroid, the main belt object now known as 2 Pallas.

In June of 1802, Olbers proposed that both Ceres and Pallas were fragments of the missing-planet and so the search for further objects in this region of the solar system continued. The German astronomer Karl Ludwig Harding (b.1765 d.1834), observing from Lilienthal, near Bremen and diligently searching the regions of Cetus and Virgo (on the basis that it was considered fragments of a disintegrated planet may be in the same region) found the third asteroid on the 1st September 1804. This was the main belt asteroid 3 Juno, named after the Roman goddess and queen of the gods.

Astronomers continued their search of and for these new objects, and after many months of careful observations, on 29th March 1807 Olbers discovered the 4th asteroid (his 2nd) in the same region as the earlier discoveries had been made. The new asteroid was named Vesta by the German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss (b.1777 d.1855) after the Roman goddess of the family and home.

However, the rate of new asteroid discoveries then slowed dramatically until 1845 with the fifth asteroid, Astraea (named after the Greek goddess of innocence and purity). It was discovered by the German amateur astronomer, and postmaster by day, Karl Ludwig Hencke (b.1973 d.1866) following 15 years of dedication, commitment and systematic observations. This reduction in discoveries was skewed by the lack of very accurate star catalogues; a general feeling (such as advised by the then director of the Paris Observatory, Jean Baptiste Delambre) that systematic stellar catalogues offered better scientific advantages; and an implied pre-disposition to look in the regions of space near to the already discovered asteroids and their orbital intersections.

Following Hencke’s discovery, new impetus was given to the search for asteroids and many more discoveries followed. Asteroid 6 Hebe was also found by Hencke in July of 1847; the first British asteroidal discoveries were 7 Iris (August 1847) and 8 Flora (October 1847) both discovered by John Russell Hind (b.1823 d.1895) from an observatory in Regents Park, London. By the end of 1850, 13 asteroids had been detected, and by 1857 a total of 50 asteroids had been discovered. These all lie in the region between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, and the asteroids found within this region are known as “main belt” asteroids.

By the start of 1867 a total of 91 asteroids had been discovered and it was in this year that the American mathematician and astronomer Daniel Kirkwood (b.1814 d.1895) identified what has become known as the ‘Kirkwood gaps’. These are areas (measured by radial distance from the Sun) where there are no asteroids to be found within the main asteroid belt. They are ‘real’ gaps and are due to gravitational resonances.

However, asteroids are not only found in the main belt region. Next month we will look at where else in the solar system these objects are. We will see how some could, and for certain historically have, hit the Earth.