31st October 1920 - The discovery of Hidalgo

On this day in 1920, Hidalgo, the first of a previously unknown class of asteroid-like objects, the Centaurs, was detected by Walter Baade (b.1893 d.1960) whilst working at the Hamburg Observatory.

Le 31 octobre 1920, Walter Baade (1893-1960) a découvert les centaures pendant qu’il travaillait à l’université de Hamburg.

For many years Hidalgo, technically named 944 Hidalgo (1920 HZ), remained an anomalous and unique object until 1977 when the second Centaur was discovered. This was Chiron (not to be confused with Charon, one of the moons of Pluto) and was found by Charles Kowal (b.1940 d.2011) through examining photographic plates taken as part of the Palomar solar system survey project. Originally designated 1977 UB, its permanent name is 2060 Chiron. Next to be found was 1991 DA (5335 Damocles). To date, 454 Centaurs have been detected, with 328 of these having been found since the beginning of the year 2010.

Les centaures sont des objets astronomiques ressemblant à des astéroïdes. Pendant longtemps Hidalgo (nommé 944 Hidalgo - 1920 HZ) restait un objet unique, jusqu'en 1977 quand un deuxième centaure serait découvert : Chiron (qu'il ne faut pas confondre avec Charon - une des lunes de Pluton). Chiron a été découvert par Charles Kowal (1940-2011) quand il était en train d’examiner des plaques photographiques de l'observatoire du Mont Palomar en Californie. D'abord nommé 1977 UB, son vrai nom est 2060 Chiron. Ensuite on a trouvé 1991 DA (5335 Damocles). A ce jour 454 centaures ont été découverts dont 328 depuis 2010.

Except for Hidalgo (which is named after a Mexican priest), proper names of the Centaurs are sourced from the half-human/half horse centaurs of Greek mythology.

A l'exception de Hidalgo (qui est nommé après un prêtre mexicain les noms des centaures proviennent des centaures de la mythologie grecque.

The Centaurs orbit predominately between the orbits of Jupiter and Neptune, and with semi-major axes ranging from ~5.5 to ~30AU. Hidalgo is on a relatively high (for the class) eccentric orbit (e = 0.66). It has a perihelion distance (of 1.95 AU) a little beyond the orbit of Mars, and an aphelion (of 9.53 AU) which is very close to the orbit of Saturn.

On this day in 1920, Hidalgo, the first of a previously unknown class of asteroid-like objects, the Centaurs, was detected by Walter Baade (b.1893 d.1960) whilst working at the Hamburg Observatory.

Le 31 octobre 1920, Walter Baade (1893-1960) a découvert les centaures pendant qu’il travaillait à l’université de Hamburg.

For many years Hidalgo, technically named 944 Hidalgo (1920 HZ), remained an anomalous and unique object until 1977 when the second Centaur was discovered. This was Chiron (not to be confused with Charon, one of the moons of Pluto) and was found by Charles Kowal (b.1940 d.2011) through examining photographic plates taken as part of the Palomar solar system survey project. Originally designated 1977 UB, its permanent name is 2060 Chiron. Next to be found was 1991 DA (5335 Damocles). To date, 454 Centaurs have been detected, with 328 of these having been found since the beginning of the year 2010.

Les centaures sont des objets astronomiques ressemblant à des astéroïdes. Pendant longtemps Hidalgo (nommé 944 Hidalgo - 1920 HZ) restait un objet unique, jusqu'en 1977 quand un deuxième centaure serait découvert : Chiron (qu'il ne faut pas confondre avec Charon - une des lunes de Pluton). Chiron a été découvert par Charles Kowal (1940-2011) quand il était en train d’examiner des plaques photographiques de l'observatoire du Mont Palomar en Californie. D'abord nommé 1977 UB, son vrai nom est 2060 Chiron. Ensuite on a trouvé 1991 DA (5335 Damocles). A ce jour 454 centaures ont été découverts dont 328 depuis 2010.

Except for Hidalgo (which is named after a Mexican priest), proper names of the Centaurs are sourced from the half-human/half horse centaurs of Greek mythology.

A l'exception de Hidalgo (qui est nommé après un prêtre mexicain les noms des centaures proviennent des centaures de la mythologie grecque.

The Centaurs orbit predominately between the orbits of Jupiter and Neptune, and with semi-major axes ranging from ~5.5 to ~30AU. Hidalgo is on a relatively high (for the class) eccentric orbit (e = 0.66). It has a perihelion distance (of 1.95 AU) a little beyond the orbit of Mars, and an aphelion (of 9.53 AU) which is very close to the orbit of Saturn.

Orbit schematic for Hidalgo and Chiron

Unlike some classes of asteroids in the solar system (i.e. the Aten and Apollo class of asteroids) the Centaurs are not NEOs (Near-Earth-Objects) or PHAs (Potentially Hazardous Asteroids). But they are on unstable orbits and have short dynamical lifetimes (1 to 10 million years) compared to the age of the solar system (~4.5 thousand million years).

Their orbits change significantly due to gravitational interactions of the major planets (which can put these objects on hyperbolic, i.e. solar system escape, paths) and collisions with the major planets and other Centaur and asteroids. This means that their individual lifetimes within the solar system are astronomically short. Hidalgo itself is edging towards a stable 2:1 resonance (with Saturn) orbit.

They have comet-like orbits and the predominant sources of these objects are most likely to be both orbital period reduction of long period comets following major planet gravitational interaction, and outward migration of asteroid belt objects under the influence (in particular) of Jupiter and Neptune. Studies (Taylor, 1982) into the gravitational effect of Jupiter on the outer-main belt have shown that a second rarefied belt of asteroids can exist between the orbits of Jupiter – Saturn.

Many centaurs can also be thought of, at least in part, as transition objects between comets and asteroids. Spectroscopic observations and analyses of both Hidalgo and Chiron would suggest that these are comet transitions, their spectra are more like comets rather than other asteroids.

However, as in all things in astronomy, the picture is not that clear as the estimated sizes of these objects (bimodal, around ~40km and in the range 140 – 170km respectively) are an order of magnitude larger than a typical comet nucleus.

Their orbits change significantly due to gravitational interactions of the major planets (which can put these objects on hyperbolic, i.e. solar system escape, paths) and collisions with the major planets and other Centaur and asteroids. This means that their individual lifetimes within the solar system are astronomically short. Hidalgo itself is edging towards a stable 2:1 resonance (with Saturn) orbit.

They have comet-like orbits and the predominant sources of these objects are most likely to be both orbital period reduction of long period comets following major planet gravitational interaction, and outward migration of asteroid belt objects under the influence (in particular) of Jupiter and Neptune. Studies (Taylor, 1982) into the gravitational effect of Jupiter on the outer-main belt have shown that a second rarefied belt of asteroids can exist between the orbits of Jupiter – Saturn.

Many centaurs can also be thought of, at least in part, as transition objects between comets and asteroids. Spectroscopic observations and analyses of both Hidalgo and Chiron would suggest that these are comet transitions, their spectra are more like comets rather than other asteroids.

However, as in all things in astronomy, the picture is not that clear as the estimated sizes of these objects (bimodal, around ~40km and in the range 140 – 170km respectively) are an order of magnitude larger than a typical comet nucleus.

25th October 1789 - Anniversary of birth of Samuel Heinrich Schwabe

Samuel Heinrich Schwabe (25/10/1789 - 11/04/1875)

Samuel Heinrich Schwabe était un astronome allemand célèbre pour son travail sur les taches solaires. Né à Dessau, une ville près de Berlin, il a commencé sa carrière en étudiant la pharmacie à l’université de Berlin. Puis en 1812 et après la mort de son père il est rentré à Dessau pour s’occuper de la pharmacie familiale mais en même temps il a poursuivi l’astronome en tant qu’amateur. Après avoir gagné un télescope en 1825 dans une loterie il s’est passionné vite pour l’observation du ciel.

Samuel Heinrich Schwabe (25/10/1789 - 11/04/1875)

Samuel Heinrich Schwabe était un astronome allemand célèbre pour son travail sur les taches solaires. Né à Dessau, une ville près de Berlin, il a commencé sa carrière en étudiant la pharmacie à l’université de Berlin. Puis en 1812 et après la mort de son père il est rentré à Dessau pour s’occuper de la pharmacie familiale mais en même temps il a poursuivi l’astronome en tant qu’amateur. Après avoir gagné un télescope en 1825 dans une loterie il s’est passionné vite pour l’observation du ciel.

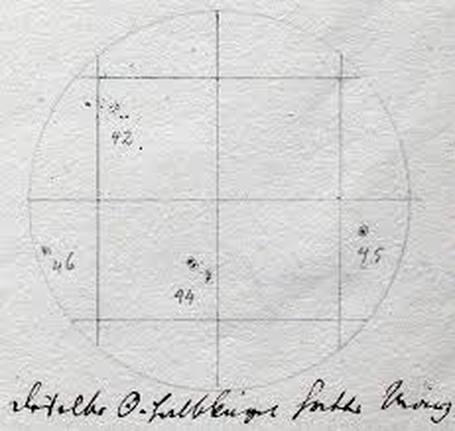

Drawing of Sun made by Schwabe on 14th April, 1847

(From further reading [1])

(From further reading [1])

Samuel Heinrich Schwabe was a German astronomer famous for his work on sunspots. Born in Dessau a town near Berlin, he studied pharmacy at the University of Berlin. Then in 1812 and after his father’s death he returned to Dessau to look after the family pharmacy, but at the same time he was studying astronomy as an amateur. After winning a telescope in 1825 in a lottery he soon became passionate about observing the skies.

En 1829 il a vendu la pharmacie pour concentrer sur l’astronomie, et il s’est mis alors à essayer de découvrir une nouvelle planète à l’intérieur de l’orbite de Mercure. Comme il est difficile d’observer trop proche du Soleil, Schwabe a decidé d’observer la surface solaire en espérant y trouver une tache qui serait la planète qu’il cherchait.

In 1829 he sold the pharmacy in order to concentrate on astronomy as he was trying to discover a new planet inside Mercury’s orbit. As it is difficult to observe too near to the Sun, Schwabe decided to observe the Sun’s surface hoping to find a spot on the Sun which would be the planet he was looking for.

De 1826 à 1843 il a observé le Soleil plus de 4 200 fois. Il ne trouva pas de planète mais il a rendu compte que les taches solaires apparaissent et disparaissent suivant un cycle d’une dizaine d’années. On peut dire qu’il était observateur infatigable et il a passé 46 années à observer le Soleil, la Lune, les planètes et comètes. Son travail a été recompensé en 1857 quand il a reçu une medaille d’or de la RAS de Londres et en1868 l’élection à la Royal Society. Il a continué à observer presque toute sa vie et il est mort à l’âge de 86 ans.

From 1826 to 1843 he observed the Sun more than 4,200 times. He didn’t find any planet, but he learned that sunspots appear and disappear in a cycle of approximately 10 years. He was a tireless observer and spent 46 years in all observing the Sun, the Moon and planets and comets. His work was rewarded when he received the gold medal of the RAS in London and in 1868 when he elected to the Royal Society. He continued to observe all his life and died at 86 years old.

Further reading:

[1] The Sunspot observations by Samuel Heinrich Schwabe, R. Arlt

http://www.aip.de/People/rarlt/papers/schwabe.pdf

[2] Sunspot positions and sizes for 1825 -1867 from the observations of Heinrich Samuel Schwabe. R. Arlt et al. MNRAS, 433, 4, 2013

En 1829 il a vendu la pharmacie pour concentrer sur l’astronomie, et il s’est mis alors à essayer de découvrir une nouvelle planète à l’intérieur de l’orbite de Mercure. Comme il est difficile d’observer trop proche du Soleil, Schwabe a decidé d’observer la surface solaire en espérant y trouver une tache qui serait la planète qu’il cherchait.

In 1829 he sold the pharmacy in order to concentrate on astronomy as he was trying to discover a new planet inside Mercury’s orbit. As it is difficult to observe too near to the Sun, Schwabe decided to observe the Sun’s surface hoping to find a spot on the Sun which would be the planet he was looking for.

De 1826 à 1843 il a observé le Soleil plus de 4 200 fois. Il ne trouva pas de planète mais il a rendu compte que les taches solaires apparaissent et disparaissent suivant un cycle d’une dizaine d’années. On peut dire qu’il était observateur infatigable et il a passé 46 années à observer le Soleil, la Lune, les planètes et comètes. Son travail a été recompensé en 1857 quand il a reçu une medaille d’or de la RAS de Londres et en1868 l’élection à la Royal Society. Il a continué à observer presque toute sa vie et il est mort à l’âge de 86 ans.

From 1826 to 1843 he observed the Sun more than 4,200 times. He didn’t find any planet, but he learned that sunspots appear and disappear in a cycle of approximately 10 years. He was a tireless observer and spent 46 years in all observing the Sun, the Moon and planets and comets. His work was rewarded when he received the gold medal of the RAS in London and in 1868 when he elected to the Royal Society. He continued to observe all his life and died at 86 years old.

Further reading:

[1] The Sunspot observations by Samuel Heinrich Schwabe, R. Arlt

http://www.aip.de/People/rarlt/papers/schwabe.pdf

[2] Sunspot positions and sizes for 1825 -1867 from the observations of Heinrich Samuel Schwabe. R. Arlt et al. MNRAS, 433, 4, 2013

10th October, 1846 - The discovery of Triton

On this day in 1846 the largest moon of Neptune, Triton, was discovered. Neptune itself had been discovered 17 days earlier and the English telescope maker William Lassell (18/06/1799 – 5/10/1880) observed the planet and searched for any moons. Lassell’s work was quickly rewarded with the discovery of the largest noon of Neptune.

It was not initially named anything more than ‘the moon of Neptune’ until the discovery in 1949 of Nereid, the 2nd largest Neptunian moon. Lassell had a particular interest in natural satellites and would later go on to discover 2 moons of Uranus (Ariel and Umbriel in 1851) and another moon of Saturn (Hyperion in 1848)

On this day in 1846 the largest moon of Neptune, Triton, was discovered. Neptune itself had been discovered 17 days earlier and the English telescope maker William Lassell (18/06/1799 – 5/10/1880) observed the planet and searched for any moons. Lassell’s work was quickly rewarded with the discovery of the largest noon of Neptune.

It was not initially named anything more than ‘the moon of Neptune’ until the discovery in 1949 of Nereid, the 2nd largest Neptunian moon. Lassell had a particular interest in natural satellites and would later go on to discover 2 moons of Uranus (Ariel and Umbriel in 1851) and another moon of Saturn (Hyperion in 1848)

Ce jour en 1846 la plus grande lune de Neptune Triton a été découverte par William Lassell, 17 jours après la découverte de Neptune. Au début Lassell n’avait pas nommé cette lune mais en 1849 il a découvert une deuxième lune de Neptune donc il fallait nommer les deux. La première devient Triton and la deuxième Nereid, la deuxième plus grande lune de Neptune. Plus tard Lassell a découvert 2 lunes d’Uranus (Ariel et Umbriel en 1851) et une autre lune de Saturne (Hyperion en 1848).

Triton est insolite. C’est une grande lune (la septième plus grande lune du Systèe solaire). Mais son orbite est rétrograde. C’est-à-dire qu’elle orbite dans le sens oppose à celui de la rotation de sa planète et dans le sens des aiguilles d’une montre. Elle a une inclinaison orbitale élevée (157 degrés à l’équateur.) On peut expliquer l’orbite de Triton par le fait que ce satellite ne s’est pas formé au même endroit que Neptune, mais a probablement été capturé par l’attraction gravitationnelle de la planète dans un passé lointain.

Triton est insolite. C’est une grande lune (la septième plus grande lune du Systèe solaire). Mais son orbite est rétrograde. C’est-à-dire qu’elle orbite dans le sens oppose à celui de la rotation de sa planète et dans le sens des aiguilles d’une montre. Elle a une inclinaison orbitale élevée (157 degrés à l’équateur.) On peut expliquer l’orbite de Triton par le fait que ce satellite ne s’est pas formé au même endroit que Neptune, mais a probablement été capturé par l’attraction gravitationnelle de la planète dans un passé lointain.

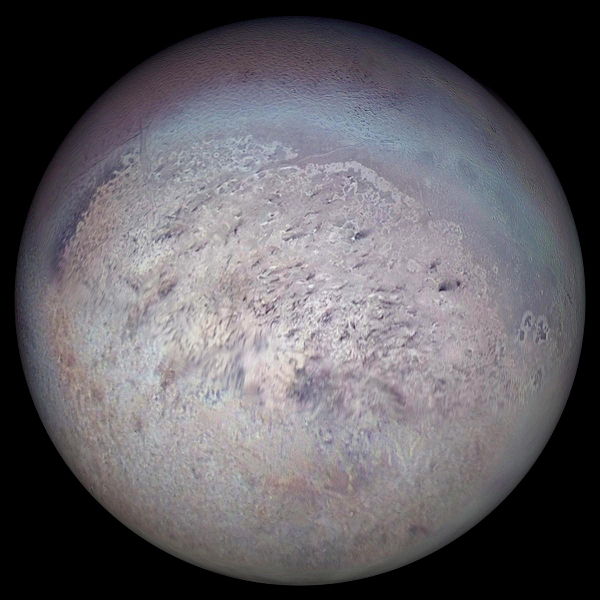

Triton is very unusual. It is a relatively large moon (the 7th largest moon in the Solar System) and approximately 78% the size (radius) our own Moon. However, its orbit is ‘retrograde’. That means that instead of orbiting Neptune in the same direction as the rotation of the planet (i.e. anti-clockwise), Triton orbits clockwise around the planet. It also has a high orbital inclination (157 degrees to Neptune’s rotational equator) and an almost perfect circular orbit (an eccentricity of 0.000016).

Its orbit can best be explained by Triton having been gravitationally captured by Neptune, with Pluto possibly also being involved in the dynamics, within the first few hundred million years of the formation of the solar system.

Its orbit can best be explained by Triton having been gravitationally captured by Neptune, with Pluto possibly also being involved in the dynamics, within the first few hundred million years of the formation of the solar system.

Composite image of Triton taken by the Voyager-2, August 1989

Courtesy of NASA

Courtesy of NASA

Much of what we know of the nature of Triton has been found out from the Voyager-2 probe which flew-passed Neptune and Triton in August, 1989. A very cold world, it nevertheless is remarkably active with cryo-volcanism. This activity is most likely driven by the internal (tidal) heating and stresses within the moon due to its very close proximity to the planet. Sub-surface oceans of hydrocarbons such as methane and ammonia are very likely to exist on Triton.

Triton orbits Neptune at a distance of just 354.8 thousand kilometres, which is closer to Neptune than our own Moon is to Earth (384.4 thousand km). Completing one orbit in a remarkably-quick 5.9 days, it has a captured rotation (which means it rotates on its axis in the same time as it takes to complete an orbit of Neptune).

Thus, like our own moon, it always presents the same face to its ‘parent’ planet. But unlike our own Moon, its orbit is slowly reducing in distance from the planet and thus in a little over 3 billion years it will disintegrate through having been pulled apart by Neptune’s gravity. This will lead to a ring-system very much like that of Saturn today. This will undoubtedly be a spectacular sight and worth sticking around for!

Triton orbits Neptune at a distance of just 354.8 thousand kilometres, which is closer to Neptune than our own Moon is to Earth (384.4 thousand km). Completing one orbit in a remarkably-quick 5.9 days, it has a captured rotation (which means it rotates on its axis in the same time as it takes to complete an orbit of Neptune).

Thus, like our own moon, it always presents the same face to its ‘parent’ planet. But unlike our own Moon, its orbit is slowly reducing in distance from the planet and thus in a little over 3 billion years it will disintegrate through having been pulled apart by Neptune’s gravity. This will lead to a ring-system very much like that of Saturn today. This will undoubtedly be a spectacular sight and worth sticking around for!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed