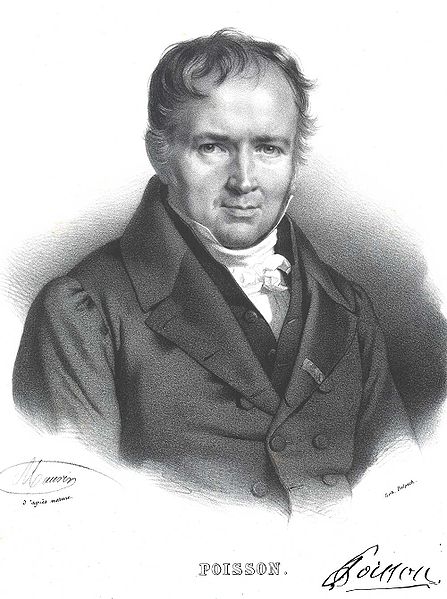

21st June - 1781 Birth-date of Siméon Denis Poisson

l'anniversaire de Siméon Denis Poisson

Today is the birthday of Siméon Denis Poisson a French mathematician and astronomer born on the 21 June 1781 in the town of Pithiviers about 80km south of Paris. Very gifted at mathematics he began his studies at the prestigious Ecole Polytechnique in Paris in 1798 at the age of 17 where was taught by Joseph Lagrange and Pierre Simon de Laplace who both noticed his talents.

Aujourd’hui c’est l’anniversaire de Siméon Denis Poisson un mathématicien et astronome français né le 21 juin 1781 dans la ville de Pithiviers à 80km au sud de Paris. Très doué pour les mathématiques il a comencé ses études à l’Ecole Polytechnique à Paris en 1798 à l’âge de 17 ans où il a suivi les cours de Joseph Lagrange et Pierre-Simon de Laplace qui ont tous deux remarqué ses talents.

Poisson loved two things: doing maths and teaching maths. So after finishing his studies he took a job as a teaching assistant at the Ecole Polytechique and later he was appointed professor of astronomy at the Bureau of Longitudes. In 1809 was became professor of rational mechanics at the Faculty of Science.

Poisson adorait deux choses: faire les mathématiques et enseigner les mathématiques. Après avoir fini ses études il a pris un poste de répétiteur à l’Ecole Polytechnique et plus tard il devient professeur d’astronomie au Bureau des Longitudes. En 1809 il est choisi comme professeur de mécanique rationale à la Faculté des Sciences.

His ‘Traité de mécanique,’ (1811 and 1833) was for a long time the work of reference on the subject, though he is especially famous for his work ‘Recherches sur la probabilité des jugements en matière criminelle et matière civile' in which we see for the first time the famous Poisson distribution. This defines the probability with which a recurring event will happen within a time period. The 'nice' thing about this distribution is that the probability of the event is independent upon the time the previous event took place. It has widespread use in natural sciences and telecommunications.

Son ‘Traité de mécanique’ (1811 and 1833) était longtemps l’ouvrage de référence mais il est surtout célèbre pour son travail, ‘Recherches sur la probabilité des jugements en matière criminelle et matière civile,' dans lequel apparaît la distribution de Poisson qui décrit la probabilité qu’un événement ait lieu pendant un intervalle de temps donné pourvu que la probabilité de réalisation d’un événement est très faible mais que le nombre d’essais est très grand.

He published 300 to 400 important papers on mathematics and he is one of the 72 experts who have their name inscribed on the Eiffel Tower, but at the time he was not particularly admired by his contempories in France. It was those mathematicians outside France who recognised the importance of his ideas. He died on 25 April 1840 in the small town of Sceaux near Paris.

Il a publié entre 300 et 400 documents importants et il est l'un des 72 savants dont le nom est inscrit sur le premier étage de la tour Eiffel. Il n’était pas tellement remarqué par ses contemporains francais mais il avait le respect des mathématiciens étrangers qui semblait reconnaître l’importance de ses idées. Il est décédé le 25 avril 1840 à Sceaux, près de Paris.

l'anniversaire de Siméon Denis Poisson

Today is the birthday of Siméon Denis Poisson a French mathematician and astronomer born on the 21 June 1781 in the town of Pithiviers about 80km south of Paris. Very gifted at mathematics he began his studies at the prestigious Ecole Polytechnique in Paris in 1798 at the age of 17 where was taught by Joseph Lagrange and Pierre Simon de Laplace who both noticed his talents.

Aujourd’hui c’est l’anniversaire de Siméon Denis Poisson un mathématicien et astronome français né le 21 juin 1781 dans la ville de Pithiviers à 80km au sud de Paris. Très doué pour les mathématiques il a comencé ses études à l’Ecole Polytechnique à Paris en 1798 à l’âge de 17 ans où il a suivi les cours de Joseph Lagrange et Pierre-Simon de Laplace qui ont tous deux remarqué ses talents.

Poisson loved two things: doing maths and teaching maths. So after finishing his studies he took a job as a teaching assistant at the Ecole Polytechique and later he was appointed professor of astronomy at the Bureau of Longitudes. In 1809 was became professor of rational mechanics at the Faculty of Science.

Poisson adorait deux choses: faire les mathématiques et enseigner les mathématiques. Après avoir fini ses études il a pris un poste de répétiteur à l’Ecole Polytechnique et plus tard il devient professeur d’astronomie au Bureau des Longitudes. En 1809 il est choisi comme professeur de mécanique rationale à la Faculté des Sciences.

His ‘Traité de mécanique,’ (1811 and 1833) was for a long time the work of reference on the subject, though he is especially famous for his work ‘Recherches sur la probabilité des jugements en matière criminelle et matière civile' in which we see for the first time the famous Poisson distribution. This defines the probability with which a recurring event will happen within a time period. The 'nice' thing about this distribution is that the probability of the event is independent upon the time the previous event took place. It has widespread use in natural sciences and telecommunications.

Son ‘Traité de mécanique’ (1811 and 1833) était longtemps l’ouvrage de référence mais il est surtout célèbre pour son travail, ‘Recherches sur la probabilité des jugements en matière criminelle et matière civile,' dans lequel apparaît la distribution de Poisson qui décrit la probabilité qu’un événement ait lieu pendant un intervalle de temps donné pourvu que la probabilité de réalisation d’un événement est très faible mais que le nombre d’essais est très grand.

He published 300 to 400 important papers on mathematics and he is one of the 72 experts who have their name inscribed on the Eiffel Tower, but at the time he was not particularly admired by his contempories in France. It was those mathematicians outside France who recognised the importance of his ideas. He died on 25 April 1840 in the small town of Sceaux near Paris.

Il a publié entre 300 et 400 documents importants et il est l'un des 72 savants dont le nom est inscrit sur le premier étage de la tour Eiffel. Il n’était pas tellement remarqué par ses contemporains francais mais il avait le respect des mathématiciens étrangers qui semblait reconnaître l’importance de ses idées. Il est décédé le 25 avril 1840 à Sceaux, près de Paris.

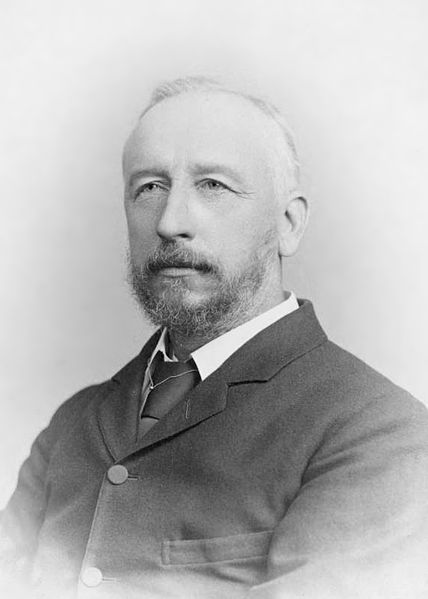

12th June - 1843 Birth-date of David Gill

l'anniversaire de David Gill

Today is the birthday of David Gill, a Scottish astronomer and son of an Aberdeen clockmaker. Although Gill was never astronomer royal for Scotland there are some who think he deserved this honour due to his many achievements. For example he won the Bruce medal; he is the only Scottish person to win the gold medal of the Royal Society twice, and he received a knighthood in 1900. What is interesting about Gill is that he did not receive a traditional scientific education. He took a clockmaking apprenticeship, and worked in his father’s shop. But he was very interested in the idea of ‘time’ which led to his passion for practical astronomy.

Aujourd’hui c’est l’anniversaire de David Gill, (1843-1914) astronome écossais et fils d’un horloger à Aberdeen. Il n’était jamais astronome royal pour l’Ecosse mais il y a ceux qui croient qu’il méritait cet honneur en raison de ses nombreuses réussites. Par exemple il a gagné la médaille Bruce; il est le seul Ecossais à gagner la médaille d’or de la Royal Society deux fois, et il a reçu le titre de chevalier en 1900. Gill est très intéressant parce qu’il n’a pas reçu l’enseignement traditionnel d’un astronome; il a pris un apprentissage d’horloger et il travaillait dans le magasin de son père. Mais il s’intéressait beaucoup à la notion du ‘temps’ ce qui a inspiré sa passion pour l’astronomie pratique.

In 1872, however, he sold his father’s shop and managed the installation of equipment at Lord Lindsay’s observatory in Dun Echt, Aberdeenshire. Then in 1874 he took part in the expedition to observe the transit of Venus from Mauritius, and in 1877 he used the parallax of Mars to determine the distance to the Sun. He was also a leading figure in the organisation of the Carte du Ciel project which aimed to map the entire sky. Despite his lack of university degrees he had the good fortune to be appointed Her Majesty’s astronomer at the Cape of Good Hope (1879-1906), and under his management the Cape observatory became a centre of excellence. He retired in 1906 and moved to London where he spent two years as president of the Royal Astronomical Society (1909-1911). After his death from pneumonia in 1914 he was buried at St Machar’s Cathedral in Aberdeen.

En 1872 il a vendu le commerce de son père pour diriger l’installation des équipements à l’observatoire de Lord Lindsay à Dun Echt, Aberdeenshire. Puis en 1874 il a participé à une expédition pour observer le transit de Vénus et en 1877 il a utilisé la parallaxe de mars pour déterminer le distance Terre -Soleil. Il a été un pionnier de l’astrophotographie et un participant majeur dans l’organisation de la Carte du Ciel. Malgré sa manque de diplômes universitaires il a été nommé astronome de Sa Majesté a la Cap de Bonne Espérance (1879-1906) et sous sa direction l’observatoire de la Cap est devenu un centre d’excellence. Ayant pris sa retraite en 1906 il a déménagé à Londres où il a passé deux ans comme président de la Royal Astronomical Society. Il est mort d’une pneumonie en 1914 à l’âge de 70 ans.

l'anniversaire de David Gill

Today is the birthday of David Gill, a Scottish astronomer and son of an Aberdeen clockmaker. Although Gill was never astronomer royal for Scotland there are some who think he deserved this honour due to his many achievements. For example he won the Bruce medal; he is the only Scottish person to win the gold medal of the Royal Society twice, and he received a knighthood in 1900. What is interesting about Gill is that he did not receive a traditional scientific education. He took a clockmaking apprenticeship, and worked in his father’s shop. But he was very interested in the idea of ‘time’ which led to his passion for practical astronomy.

Aujourd’hui c’est l’anniversaire de David Gill, (1843-1914) astronome écossais et fils d’un horloger à Aberdeen. Il n’était jamais astronome royal pour l’Ecosse mais il y a ceux qui croient qu’il méritait cet honneur en raison de ses nombreuses réussites. Par exemple il a gagné la médaille Bruce; il est le seul Ecossais à gagner la médaille d’or de la Royal Society deux fois, et il a reçu le titre de chevalier en 1900. Gill est très intéressant parce qu’il n’a pas reçu l’enseignement traditionnel d’un astronome; il a pris un apprentissage d’horloger et il travaillait dans le magasin de son père. Mais il s’intéressait beaucoup à la notion du ‘temps’ ce qui a inspiré sa passion pour l’astronomie pratique.

In 1872, however, he sold his father’s shop and managed the installation of equipment at Lord Lindsay’s observatory in Dun Echt, Aberdeenshire. Then in 1874 he took part in the expedition to observe the transit of Venus from Mauritius, and in 1877 he used the parallax of Mars to determine the distance to the Sun. He was also a leading figure in the organisation of the Carte du Ciel project which aimed to map the entire sky. Despite his lack of university degrees he had the good fortune to be appointed Her Majesty’s astronomer at the Cape of Good Hope (1879-1906), and under his management the Cape observatory became a centre of excellence. He retired in 1906 and moved to London where he spent two years as president of the Royal Astronomical Society (1909-1911). After his death from pneumonia in 1914 he was buried at St Machar’s Cathedral in Aberdeen.

En 1872 il a vendu le commerce de son père pour diriger l’installation des équipements à l’observatoire de Lord Lindsay à Dun Echt, Aberdeenshire. Puis en 1874 il a participé à une expédition pour observer le transit de Vénus et en 1877 il a utilisé la parallaxe de mars pour déterminer le distance Terre -Soleil. Il a été un pionnier de l’astrophotographie et un participant majeur dans l’organisation de la Carte du Ciel. Malgré sa manque de diplômes universitaires il a été nommé astronome de Sa Majesté a la Cap de Bonne Espérance (1879-1906) et sous sa direction l’observatoire de la Cap est devenu un centre d’excellence. Ayant pris sa retraite en 1906 il a déménagé à Londres où il a passé deux ans comme président de la Royal Astronomical Society. Il est mort d’une pneumonie en 1914 à l’âge de 70 ans.

7th / 8th June 1918 - A spectacular nova

Une nova spectaculaire!

One hundred years ago today, on the night of the 7th / 8th June 1918, a previously very faint star became one of the brightest stars visible in the night sky. The star, named V603 Aql in the constellation of Aquila (the Eagle), one of the 48 constellations described by Ptolemy, had become a nova. Novae (from the Latin for new), and first applied to astronomical events by the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe in his book of 1573, De Nova Stella, are stars which rapidly increase in brightness for a few days and then fade relatively quickly to their previous brightness, or fainter.

Il y a 100 ans aujourd’hui pendant la nuit du 7/8 juin 1918 une étoile nommée v603Aql dans la constellation d’Aquila (l’Aigle), l’une des 48 constellations décrite par Ptolémy, est devenue une nova. Les Novae (du Latin pour ‘nouveau’) sont des étoiles normales qui deviennent rapidement plus brillantes et après quelques jours l'étoile reprend ensuite progressivement son éclat initial.

The star increased from being invisible to the naked eye (at magnitude ~ +11.4) to being almost as bright as Sirius, visually the brightest star we see with our eyes in the night sky. V603 had increased to at least magnitude -1.1, and possibly as bright as -1.4 by the 9th of June. Sirius’s magnitude is -1.46. Within 10 days it had faded to be about the same brightness as the star Polaris, and by the 20th November 1918 it was only just discernible to the naked eye.

Cette étoile qui avait été presque invisible à l’oeil nu (magnitude +11.4) est devenue presqu’aussi brillante que Sirius et a atteint une minimale (correspondant à une luminosité maximale) de -1,4. La magnitude de Sirius est -1.46.

The star was visually the brightest nova to have been seen for at least 1000 years. The Crab nebula seen in Taurus in 1054 by Chinese astronomers, Brahe’s 1572 observation of the new-star in Cassiopeia and Johannes Kepler’s 1604 observation of the new-star in Ophiuchus were all of supernovae; which are very different to novae.

Pendant 1000 ans l’étoile était la nova la plus lumineuse. La nébuleuse du crabe vue en 1054 par des astronomes chinois, dans la constellation du Taurau était une supernova qui est très différente d’une nova.

The nova was detected and observed across all parts of the Earth. It appears to have been almost simultaneously detected first by the Indian astronomer Radha Gobinda Chandra (1878 – 1975) and the Polish astronomer Zygmunt Laskowski (1841 – 1928). It was certainly confirmed by Grace Cook (1877 – 1958) in England. Cook was one of the first group of ladies to be elected, in 1916, to fellowship of the Royal Astronomical Society. Immediate follow-up observations were taken by many observers across all of Europe and the US; with Alphonse Borrelly and Henry Bourget at the Observatoire de Marseille, and Marcel Moye at Montpellier, taking many measurements. [*1]

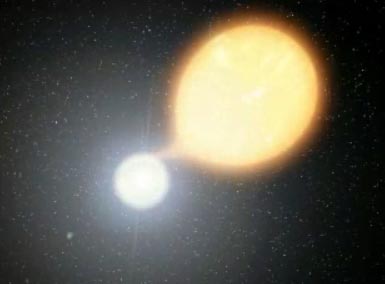

V603 is a good example of a ‘classical nova’. Many stars are variable in their brightness and emissions, and classical nova are a type of variable star know as ‘Cataclysmic Variables’. In the case of classical novae, we have 2 stars revolving around each other. One of the stars is an evolved star known as a white dwarf, whereas the other star is larger in size, but less massive. They have a close orbit and material from the larger sized star is gravitationally disrupted and ‘falls’ onto the surface (via an accretion disc) of the (degenerate) white dwarf. After a relatively brief time, a few thousand years, the material accumulated on the surface of the white dwarf becomes sufficiently dense, heated and pressurised for unconstrained nuclear fusion of the material to initiate. The resultant ‘explosion’ is what we see as the nova. Neither star is destroyed by the event and the process can reoccur.

Une nova spectaculaire!

One hundred years ago today, on the night of the 7th / 8th June 1918, a previously very faint star became one of the brightest stars visible in the night sky. The star, named V603 Aql in the constellation of Aquila (the Eagle), one of the 48 constellations described by Ptolemy, had become a nova. Novae (from the Latin for new), and first applied to astronomical events by the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe in his book of 1573, De Nova Stella, are stars which rapidly increase in brightness for a few days and then fade relatively quickly to their previous brightness, or fainter.

Il y a 100 ans aujourd’hui pendant la nuit du 7/8 juin 1918 une étoile nommée v603Aql dans la constellation d’Aquila (l’Aigle), l’une des 48 constellations décrite par Ptolémy, est devenue une nova. Les Novae (du Latin pour ‘nouveau’) sont des étoiles normales qui deviennent rapidement plus brillantes et après quelques jours l'étoile reprend ensuite progressivement son éclat initial.

The star increased from being invisible to the naked eye (at magnitude ~ +11.4) to being almost as bright as Sirius, visually the brightest star we see with our eyes in the night sky. V603 had increased to at least magnitude -1.1, and possibly as bright as -1.4 by the 9th of June. Sirius’s magnitude is -1.46. Within 10 days it had faded to be about the same brightness as the star Polaris, and by the 20th November 1918 it was only just discernible to the naked eye.

Cette étoile qui avait été presque invisible à l’oeil nu (magnitude +11.4) est devenue presqu’aussi brillante que Sirius et a atteint une minimale (correspondant à une luminosité maximale) de -1,4. La magnitude de Sirius est -1.46.

The star was visually the brightest nova to have been seen for at least 1000 years. The Crab nebula seen in Taurus in 1054 by Chinese astronomers, Brahe’s 1572 observation of the new-star in Cassiopeia and Johannes Kepler’s 1604 observation of the new-star in Ophiuchus were all of supernovae; which are very different to novae.

Pendant 1000 ans l’étoile était la nova la plus lumineuse. La nébuleuse du crabe vue en 1054 par des astronomes chinois, dans la constellation du Taurau était une supernova qui est très différente d’une nova.

The nova was detected and observed across all parts of the Earth. It appears to have been almost simultaneously detected first by the Indian astronomer Radha Gobinda Chandra (1878 – 1975) and the Polish astronomer Zygmunt Laskowski (1841 – 1928). It was certainly confirmed by Grace Cook (1877 – 1958) in England. Cook was one of the first group of ladies to be elected, in 1916, to fellowship of the Royal Astronomical Society. Immediate follow-up observations were taken by many observers across all of Europe and the US; with Alphonse Borrelly and Henry Bourget at the Observatoire de Marseille, and Marcel Moye at Montpellier, taking many measurements. [*1]

V603 is a good example of a ‘classical nova’. Many stars are variable in their brightness and emissions, and classical nova are a type of variable star know as ‘Cataclysmic Variables’. In the case of classical novae, we have 2 stars revolving around each other. One of the stars is an evolved star known as a white dwarf, whereas the other star is larger in size, but less massive. They have a close orbit and material from the larger sized star is gravitationally disrupted and ‘falls’ onto the surface (via an accretion disc) of the (degenerate) white dwarf. After a relatively brief time, a few thousand years, the material accumulated on the surface of the white dwarf becomes sufficiently dense, heated and pressurised for unconstrained nuclear fusion of the material to initiate. The resultant ‘explosion’ is what we see as the nova. Neither star is destroyed by the event and the process can reoccur.

An artist’s impression of a classical nova

Image used courtesy of and credit to NASA/JPL-Caltech

https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/galex/image-galex-nova-20070307.html

Image used courtesy of and credit to NASA/JPL-Caltech

https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/galex/image-galex-nova-20070307.html

In the case of V603, spectroscopic and radial velocity observations and analyses [*2] have shown the components to be a white dwarf of mass ~1.2 times that of our sun, and a low mass star of mass ~0.29 times that of our sun. They orbit around their mutual centre of gravity once every 3hrs 20mins and so are most likely to be only semi-detached, and a near-contact system. (Recall that a white dwarf star is very small, typically only about the same size as the Earth). The components are unresolvable which means they cannot be visually seen as separate stars even by the largest of our telescopes.

The Hubble space telescope was used to determine the parallax of the system [*3] and thus the distance to V603 can be estimated as ~249 parsecs (or ~812 light years)

In the case of V603 its current brightest is now less than its pre-eruption magnitude. This is likely to be due to instabilities of the accretion disc within the system.

Nova are rare, but within the milky way we can see around ten per year. However, none that we have seen have been as spectacular at the event one hundred years ago today. (Yet!)

References and further reading

[1] Contemporaneous observations (Campbell 1919)

http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1923AnHar..81..113C

[2] ESO Spectroscopic observations and analyses (Arenas et al 2000)

http://adsbit.harvard.edu//full/2000MNRAS.311..135A/0000135.000.html

[3] Hubble Space Telescope parallax observations (Harrison et al 2013)

http://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/0004-637X/767/1/7/meta

The Hubble space telescope was used to determine the parallax of the system [*3] and thus the distance to V603 can be estimated as ~249 parsecs (or ~812 light years)

In the case of V603 its current brightest is now less than its pre-eruption magnitude. This is likely to be due to instabilities of the accretion disc within the system.

Nova are rare, but within the milky way we can see around ten per year. However, none that we have seen have been as spectacular at the event one hundred years ago today. (Yet!)

References and further reading

[1] Contemporaneous observations (Campbell 1919)

http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1923AnHar..81..113C

[2] ESO Spectroscopic observations and analyses (Arenas et al 2000)

http://adsbit.harvard.edu//full/2000MNRAS.311..135A/0000135.000.html

[3] Hubble Space Telescope parallax observations (Harrison et al 2013)

http://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/0004-637X/767/1/7/meta

5th June - Birthday of John Couch Adams

l’anniversaire de John Couch Adams,

Today is the birthday of John Couch Adams, the son of a tenant farmer born in Cornwall on the 5th June 1819. Adams was a British astronomer who loved maths and astronomy books from a very young age. Born into a family of modest means he worked as a private tutor to help finance his studies at St John’s College Cambridge; luckily he was also awarded a bursary and at the same time his mother received a small inheritance.

Aujourd’hui c’est l’anniversaire de John Couch Adams, le fils d'un métayer né dans les Cornouailles le 5 juin 1819. Adams était un astronome britannique qui adorait très jeune les maths et les livres d'astronomie. Issu d’une famille modeste il donnait des leçons particulières pour continuer ses études à St John’s College Cambridge; en même temps sa mère a reçu un petit héritage et il a gagné une bourse d’études.

He is famous for predicting the existence and the position of the planet Neptune by using just mathematics. Sadly for Adams the French astronomer Urbain le Verrier (1811-1877) had done the same calculations. But Le Verrier had asked Johann Gottgried Galle to locate the planet with his telescope in the sky which Galle did in September 1846 at the Berlin Observatory. Both Adams and Le Verrier received the prestigious Copley Medal of the Royal Society in London for their discovery. But it was Le Verrier who was declared the official discoverer of the planet. Adams, a modest man, (so modest he turned down a knighthood), congratulated the French man stating,

'...there is no doubt that his researches were first published to the world and led to the actual discovery of the planet by Dr Galle so that the fact stated above cannot detract in the slightest degree, from the credit due to M Le Verrier.’

Il est célèbre pour sa prédiction de l’existence et la position de la planète Neptune en se basant uniquement sur les mathematiques. Malheureusement pour Adams l’astronome français Urbain le Verrier avait fait les mêmes calculs et Le Verrier a demandé à son collègue Johann Gottgried Galle de localiser la planète au télescope dans le ciel et Galle a trouvé la planète en septembre 1846 à l'observatoire de Berlin. Adams et Le Verrier ont reçu la Médaille Copley (Adams en 1848) de la Royal Society de Londres qui est la médaille la plus prestigieuse et la plus ancienne attribuée par la Royal Society. Mais c’est Le Verrier qui sera déclaré découvreur officiel de la planète. Adams salua, d'ailleurs, ouvertement la primauté de Le Verrier et il a dit:

‘car il n'y a pas de doute que ses recherches ont été rendues publiques en premier et ont conduit à la découverte de la planète par le Dr Galle. Les faits énoncés ci-dessus n'enlèvent rien au crédit de M. Le Verrier.'

Among his successes Adams described the movement of the Moon more precisely than Simon Laplace and was appointed director of the Cambridge Observatory from 1861. He married in 1863 and led a happy life until he died in Cambridge on 21st January 1892 after a long illness.

Parmi ses réussites Adams a decrit la motion de la Lune plus précisement que Simon LaPlace et il est directeur de l'observatoire de Cambridge à partir de 1861. Il est décédé à Cambridge le 21 janvier 1892 à la suite une longue maladie

l’anniversaire de John Couch Adams,

Today is the birthday of John Couch Adams, the son of a tenant farmer born in Cornwall on the 5th June 1819. Adams was a British astronomer who loved maths and astronomy books from a very young age. Born into a family of modest means he worked as a private tutor to help finance his studies at St John’s College Cambridge; luckily he was also awarded a bursary and at the same time his mother received a small inheritance.

Aujourd’hui c’est l’anniversaire de John Couch Adams, le fils d'un métayer né dans les Cornouailles le 5 juin 1819. Adams était un astronome britannique qui adorait très jeune les maths et les livres d'astronomie. Issu d’une famille modeste il donnait des leçons particulières pour continuer ses études à St John’s College Cambridge; en même temps sa mère a reçu un petit héritage et il a gagné une bourse d’études.

He is famous for predicting the existence and the position of the planet Neptune by using just mathematics. Sadly for Adams the French astronomer Urbain le Verrier (1811-1877) had done the same calculations. But Le Verrier had asked Johann Gottgried Galle to locate the planet with his telescope in the sky which Galle did in September 1846 at the Berlin Observatory. Both Adams and Le Verrier received the prestigious Copley Medal of the Royal Society in London for their discovery. But it was Le Verrier who was declared the official discoverer of the planet. Adams, a modest man, (so modest he turned down a knighthood), congratulated the French man stating,

'...there is no doubt that his researches were first published to the world and led to the actual discovery of the planet by Dr Galle so that the fact stated above cannot detract in the slightest degree, from the credit due to M Le Verrier.’

Il est célèbre pour sa prédiction de l’existence et la position de la planète Neptune en se basant uniquement sur les mathematiques. Malheureusement pour Adams l’astronome français Urbain le Verrier avait fait les mêmes calculs et Le Verrier a demandé à son collègue Johann Gottgried Galle de localiser la planète au télescope dans le ciel et Galle a trouvé la planète en septembre 1846 à l'observatoire de Berlin. Adams et Le Verrier ont reçu la Médaille Copley (Adams en 1848) de la Royal Society de Londres qui est la médaille la plus prestigieuse et la plus ancienne attribuée par la Royal Society. Mais c’est Le Verrier qui sera déclaré découvreur officiel de la planète. Adams salua, d'ailleurs, ouvertement la primauté de Le Verrier et il a dit:

‘car il n'y a pas de doute que ses recherches ont été rendues publiques en premier et ont conduit à la découverte de la planète par le Dr Galle. Les faits énoncés ci-dessus n'enlèvent rien au crédit de M. Le Verrier.'

Among his successes Adams described the movement of the Moon more precisely than Simon Laplace and was appointed director of the Cambridge Observatory from 1861. He married in 1863 and led a happy life until he died in Cambridge on 21st January 1892 after a long illness.

Parmi ses réussites Adams a decrit la motion de la Lune plus précisement que Simon LaPlace et il est directeur de l'observatoire de Cambridge à partir de 1861. Il est décédé à Cambridge le 21 janvier 1892 à la suite une longue maladie

RSS Feed

RSS Feed